The Paradox of the Modern Fisherman

Picture the scene. It's dawn, and a veil of mist dances across the still surface of the water. On the shore, a carp angler is at the center of his technological universe. High-modulus carbon rods costing hundreds of euros each, reels with drags accurate to the gram, and bite alarms that communicate wirelessly with a control unit in the tent.

The air smells of boilies, baits carefully crafted to attract the record-breaking specimen. Everything is ready. Thousands of euros worth of equipment, years of experience, and hours of preparation are concentrated in this moment, waiting for a single, decisive signal.

Yet, within this symphony of technology and dedication lies a paradox as vast as it is ignored. The entire success of this enterprise, the outcome of this almost mystical wait, hinges on a single point of contact that costs less than a cup of coffee: the tip of a fishing line.

This is where the most uncomfortable and powerful truth of our world lies: the real difference between a deadly catch and a successful one is not the carbon rod or the scientific lure, but that tiny sliver of sharp metal.

What do a surgeon preparing for open-heart surgery, a Formula 1 driver feeling the traction of his tires on the asphalt, and a carp fishing master about to cast have in common?

The answer is simple: an almost maniacal obsession with the critical contact point, the one element that translates all preparation into success. The world of modern carp fishing, however, has developed a curious blind spot.

The proliferation of complex and expensive equipment has generated a cognitive bias: our attention and budget are drawn to the most visible, largest, and most commercialized items. A €500 rod seems intrinsically more valuable than a 50-cent hook.

This mismatch in perception leads us to overlook the most fundamental and impactful component, mistakenly believing that high-end technology can compensate for a fundamental weakness. But physics, as we'll see, is uncompromising. This article is a journey to illuminate that blind spot, to redefine the hook not as a disposable consumer good, but as the most critical piece of precision engineering in every fisherman's arsenal.

Anatomy of a Failure: Brutal Physics Versus a Perfect Hook

We follow the journey of a single hook, from the moment it leaves its sealed package until it lies waiting on the seabed. It's a violent journey, an odyssey of degradation that unfolds in a matter of seconds, mostly invisible to our eyes.

The Takeoff: The Illusion of Perfection

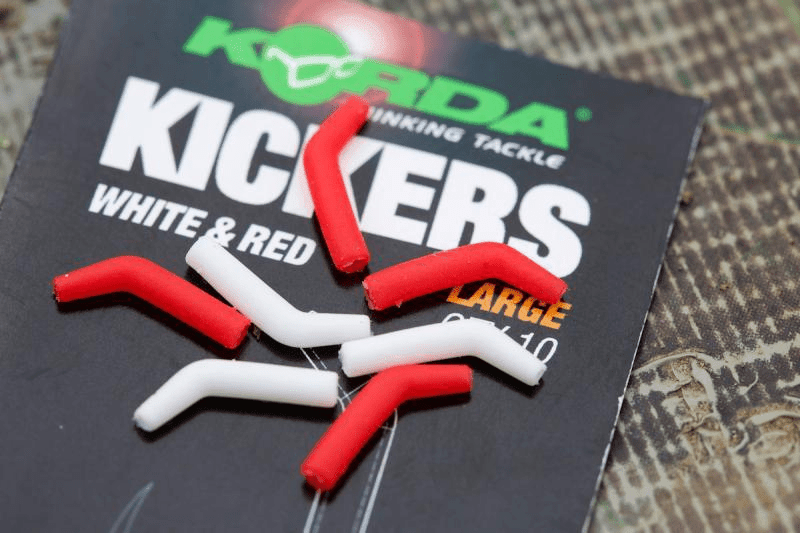

The ritual is familiar. A new bag of hooks is opened. Inside, small, perfect metal jewels. The chemically sharpened tip gleams in the light. It's so sharp it almost disappears. The PTFE or Teflon coating is flawless, smooth to the touch.

At this moment, the hook is at 100% of its potential. It's a promise of efficiency, a surgical weapon ready to perform its duty. The angler's confidence is at its peak. But this perfection is a fleeting illusion, a snapshot destined to vanish at the first contact with reality.

The Impact: 100 km/h Against a Wall of Water

The cast is powerful, the line whistling through the guides. The 120-gram lead drags the leader toward the horizon. At a distance of 70-80 meters, the lead and hook combination hits the surface at a speed that can reach 100 km/h.

At this speed, water isn't the yielding liquid we imagine. Its surface tension offers enormous and instantaneous resistance. The water molecules can't move fast enough, creating a violent and localized pressure spike right at the infinitesimal tip of the hook.

To understand the force at play, think of the sharp pain of belly-flopping in a swimming pool, or the power of a pressure washer to peel off paint. That impact is the first, brutal shock. Invisible to the human eye, it can be enough to "roll" the point, that is, bend its tip by a few microns, or blunt it, flattening its geometric perfection. The hook has already lost a critical fraction of its effectiveness, even before it begins its descent.

The Descent: A Storm of Silent Abrasions

The journey to the bottom doesn't take place in a sterile vacuum. The water column is a soup of suspended particles: very fine silt, grains of sand, microscopic organic debris.

As the lead drags the hook down the line at a speed that can still reach 20 km/h, each of these particles acts like an abrasive projectile. It's a micro-sandblasting process.

A single grain is insignificant, but thousands of collisions during the meters of descent act like very fine-grained sandpaper, slowly eroding the cutting edge of the tip and its faces. Surgical perfection turns into a slightly rougher, less efficient surface.

The Landing: The Silent Crash Test on the Ocean Floor

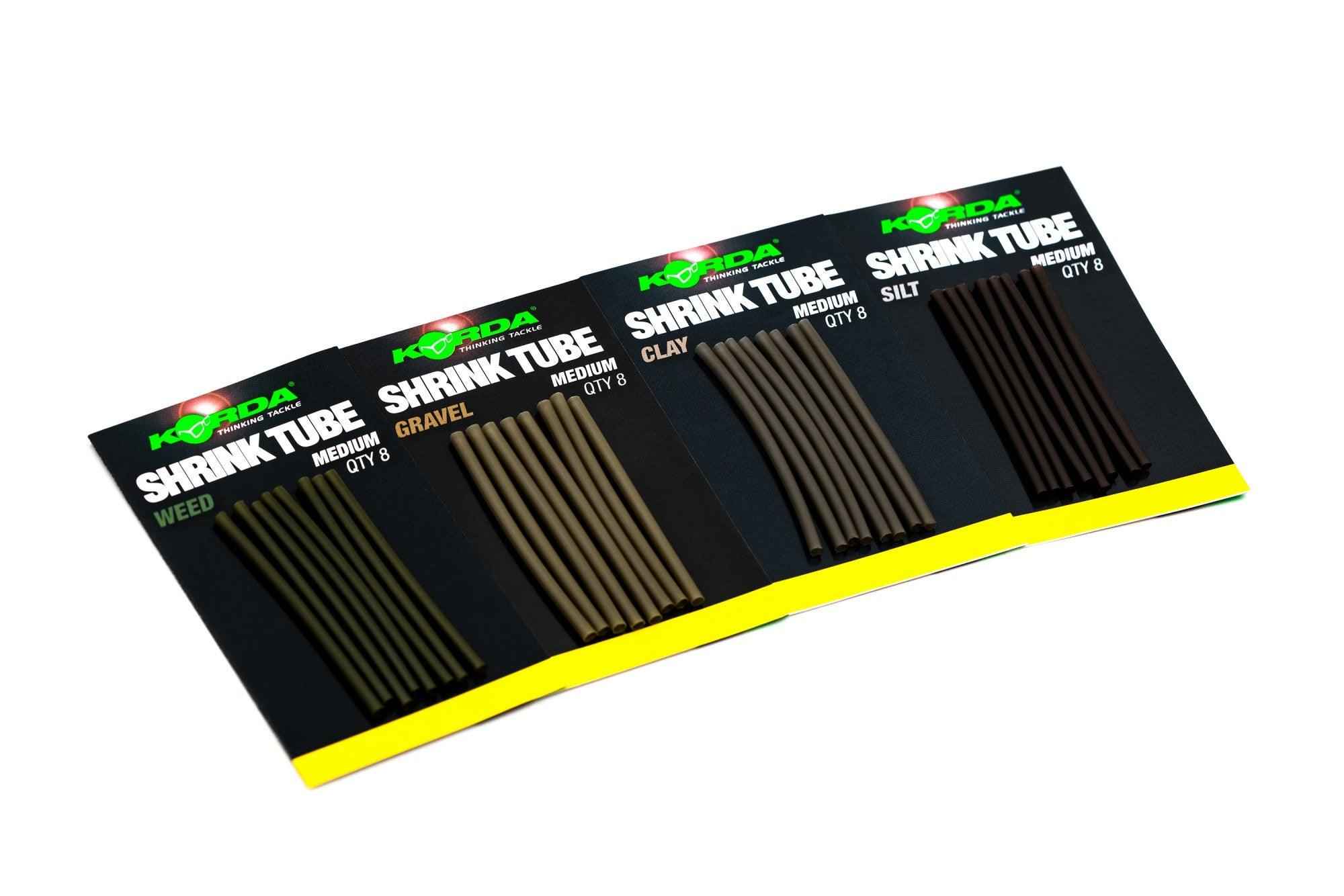

Landing on the bottom is the most critical moment, a true crash test that is repeated with every cast. The nature of the seabed determines the type and severity of the damage:

-

Gravel: This is a minefield. The impact isn't a single event, but a series of chaotic collisions against hard, sharp edges. The tip can be chipped, bent, or completely "rolled" in a fraction of a second.

-

Sand/Clay: Although they appear soft, these substrates are extremely abrasive. If the lead, due to inertia, drags the leader even a few centimeters, the effect is like rubbing the hook point on sandpaper.

-

Hard/Rocky Bottom: The worst-case scenario. The impact is a sharp "metal against rock," the equivalent of hitting the point with a hammer. The damage can be catastrophic and instantaneous, rendering the hook completely useless with a single unfortunate cast.

The Recovery: The Underwater Stations of the Cross

If there hasn't been a bite, the final stage of torture begins: the retrieve. The angler, with his rod held high, begins cranking the reel. Before the lead lifts from the bottom, the leader and hook are dragged and bounced for meters on hostile terrain. Every feature of the bottom becomes a threat:

-

Zebra mussels: Their shells are not only hard, but razor-sharp. A single contact can deeply cut the hook's point, creating a groove that compromises its ability to penetrate.

-

Submerged Branches: These act like coarse-grained files, scraping away metal and protective coating.

-

Pebbles and Debris: Every jolt we feel on the rod tip is a violent impact on the hook point, another opportunity to dull, bend, or break it.

This analysis reveals a fundamental truth: sharpness is not a static property, but a rapidly depreciating asset. From the moment the hook leaves the bag, its value (its effectiveness) is in a state of constant decay.

We're not fishing with a "sharp hook," but with a hook that's at a certain percentage of its maximum potential. A hook can be 100% in the bag, 95% after impact with the water, 90% after descending, 70% after landing on the gravel, and 50% after a single retrieve.

The goal, therefore, is not just to start with a sharp hook, but to ensure it is as close to 100% sharp as possible at the critical moment when the carp takes the bait. This makes constant checking and maintenance not an option, but an absolute necessity.

The Finger, the Nail, and the Magnifying Glass: Recognizing a Compromised Hook

If degradation is an invisible process, how can we diagnose it? There are techniques, from basic to professional, that every carp angler should master to assess the true condition of the most important weapon at their disposal.

The Nail Test: The ABCs of Carp Fishing, But It's Not Enough

This is the most well-known and practiced test: the hook point is gently placed on the surface of the thumbnail and attempted to slide. If the point bites the thumbnail and immediately catches, the hook is considered sharp. If it slips, it's dull. This test is a good starting point, a quick "go/no go" check, but it has significant limitations. It primarily checks the integrity of the tip of the point, but it cannot detect more subtle defects. A "rolled" point, whose tip is folded back on itself, may still feel "sticky" to the thumbnail, but its compromised geometry will prevent it from effectively penetrating the fish's mouth when hooking.

The Touch Test: Developing a Surgeon's Sensitivity

A more advanced technique, requiring practice and sensitivity, involves using the pad of your finger. By very delicately running the pad (not the tip) along the sides of the hook's point, you can feel imperfections that the nail test misses. You can feel tiny metal burrs, small chips, or the irregularities of a tip that has begun to warp. Developing this tactile sensitivity is like a mechanic feeling an engine or a musician feeling their instrument: it's a deeper level of connection with your equipment.

The Jeweler's Eye: The Truth Revealed by Magnification

The definitive method, one that leaves no room for doubt or interpretation, is visual inspection under magnification. Using a jeweler's loupe or a specialized hook viewer is the only way to see the truth. Under the magnifying glass, reality appears clear and irrefutable. You can distinguish a perfectly conical and sharp point from one that, to the flawless naked eye, appears rounded like a pebble. You can observe the chips left by impact with gravel, the faces abraded by dragging on the sand, or the slightest lateral deviation caused by an impact. Magnification transforms conjecture into certainty and provides the precise diagnosis needed to decide the next step.

The Existential Choice: To Change or To Sharpen? A Cost-Benefit, Soul-Based Analysis

Once a hook is diagnosed as less than perfect, the carp angler is faced with a choice: replace it with a new one or bring it back to life through sharpening? This isn't just a financial choice, but a decision that defines the very approach to the discipline.

The Substitution Economy: The Path to Convenience

The replacement logic is simple and appealing. You discard the used hook and attach a new one, fresh from the bag. The process is quick, takes just a few seconds, and ensures you always have a hook with a standard factory sharpness. It's the "consumer" approach: you use a product and, when it's no longer performing at its best, you discard it for a new one. It's a choice based on convenience and the pursuit of basic certainty, without complications.

The Art of Rebirth: Why Sharpening Is a Superior Act

The alternative is sharpening. At first glance, it might seem like a way to "save a few bucks," but this view is incredibly reductive. Sharpening a hook is an act of mastery, taking complete control over the most critical detail of your fishing. Therein lies a secret known only to the most meticulous fishermen: a hand-sharpened hook can achieve a level of sharpness and perfection far superior to that of a brand-new hook.

Mass-produced chemically sharpened points are a compromise between sharpness, durability during transport, and user safety. An angler who sharpens his own hooks, however, has no such constraints. He can create a longer, thinner point with more aggressive angles, transforming a good hook into a surgical weapon customized for a specific fishing situation. This process elevates the angler from a simple user of equipment to a true craftsman.

It's an act that creates a profound connection with your tools, transforming a mass-produced object into a unique piece, perfected by your own hands for a specific purpose. It's not about saving money, but about investing time and skill to achieve a performance advantage that can't be bought.

Comparison Table: The Dilemma in Brief

To clearly visualize the differences between the two approaches, the following table summarizes the key points:

| Characteristic | Amo Replacement (Consumer Approach) |

Hook Sharpening (Artisan Approach) |

| Speed | Maximum: seconds to replace. | Medium: Requires 1-2 minutes of precise work. |

| Long Term Cost | High: The cost of hundreds of hooks adds up. | Low: Initial investment in quality tools. |

| Maximum Performance | Standard: Good, limited by factory standard. | Superior: “Surgical” sharpening potential, beyond factory specifications. |

| Control over the Outcome | Nobody: you trust the manufacturer blindly. | Total: customization of tip angle, length and fineness. |

| Environmental Impact | Major: Contributes to metal waste. | Minor: Extends the life of each hook. |

| Connection to Discipline | Low: a mechanical and repetitive gesture. | High: An act of skill, dedication, and deep understanding. |

The Carp Angler's Workshop: Tools of the Precision Trade

Embracing the artisan's path requires not only willpower, but also the right tools. Sharpening is a precision art that tolerates no improvisation.

The File and the Stone: The Weapons of Precision

The essential tools are diamond files and sharpening stones. The files, with varying grits, are used to remove metal and reshape the tip geometry, creating the faces and defining the angle. The finer stones are used for final polishing, removing any microburrs and achieving a glass-smooth surface, ensuring maximum penetration.

The Stability Problem: The Human Hand and Its Intrinsic Limits

Here lies the greatest challenge. Holding a small, slippery object like a hook in one hand while applying a file with perfectly consistent pressure and angle with the other is a nearly impossible feat. The human hand, even the steadiest, is prone to micro-tremors. Even the slightest wobble can ruin the work, creating a rounded rather than sharp point, or irregular edges that compromise its effectiveness. This inherent instability is the main reason why many fishermen, despite understanding its importance, give up sharpening, frustrated by inconsistent results.

The Ultimate Solution: The Precision Clamp That Eliminates Human Error

The solution to this fundamental problem is a piece of engineering designed specifically for this purpose: a precision vice. This is where a tool like the Nash Pinpoint Precision Sharpening Vice comes in. This is not a simple stand, but a device that transforms sharpening from an uncertain art to a repeatable science.

Its locking mechanism holds the hook in a tight grip, eliminating any movement or vibration. No more loose points, no more inaccurate sharpening. With the hook locked in place, the angler's hand is free to focus solely on the movement of the file, maintaining a constant angle and even pressure. The clamp design allows the hook to be rotated and accessed on every side with ease, ensuring symmetrical and controlled work.

The introduction of such a tool is a game changer. It demystifies the process, making it accessible to anyone with the dedication to learn. By eliminating the most unpredictable variable—human instability—the vise allows every angler to unlock their "beyond-the-factory" sharpening potential. It transforms a skill for a select few into a methodical and reliable process, the result of which is a matter of practice, not innate talent.

From Fisherman to Master

We've followed the hook's journey: from its illusory perfection in the packaging, through the brutal physical reality of casting and retrieving, to the realization that true performance isn't bought, but created. We've seen how to diagnose invisible damage and analyzed the profound choice between consumer convenience and the artisan's dedication.

The final message is clear: the difference between a good fisherman and a great master lies not in the economic value of his equipment, but in his obsession with the details that truly matter. The last millimeter of the hook's point is the ultimate expression of this philosophy. It's the point where preparation, knowledge, and manual skill converge to transform a possibility into a certainty.

Taking care of this detail isn't just about increasing your catch. It means elevating your practice, refusing to leave anything to chance, and taking complete control of your success. It's the final step in the evolution from angler to master of your discipline.

Conclusion

You've invested in rods, reels, and bite alarms. Now it's time to invest in the one millimeter that makes them all effective. Are you ready to stop hoping and start guaranteeing every hook? Every last millimeter is in your hands.

![L'Ultimo Millimetro: La Scienza Nascosta che i carpisti trascurano [e non va bene!] - Carpela](http://carpela.it/cdn/shop/articles/lultimo-millimetro-la-scienza-nascosta-che-i-carpisti-trascurano-e-non-va-bene-4748791.jpg?v=1759800722&width=1056)